Warp Speed in Mecrisp-Stellaris

Mecrisp-Stellaris Forth is an implementation of the Forth programming language for Arm Cortex microcontrollers. It is fast, small and elegant, and was clearly well designed. I use it in my teaching, and it’s my preferred implementation of the Forth programming language.

It can be downloaded from Sourceforge and has installation candidates for a wide range of microcontrollers. I use the STM32f103RB processor in the Olimex STM32p103 board, and sometimed the blue pill STM32f103 boards.

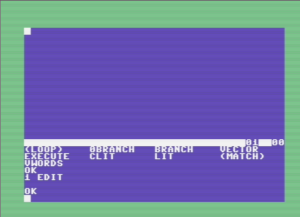

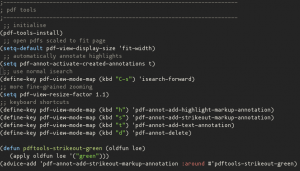

Out of the box, mecrisp uses the internal oscillator on the chip to run at 8 MHz. This is OK, but using the onboard PLL, you should be able to operate the chip at 72 MHz. That’s much more like it. I wanted to be able to do this, so started looking at the unofficial mecrisp guide, a site set up by Terry Porter to accumulate information about mecrisp, and about the closest thing it has to documentation. What I wanted to do was to start with the standard mecrisp forth for this processor, in a file called stm32f103rb.bin, and then add several words including this one, so I had some useful routines on the chip. Mecrisp forth makes this very easy by having two built-in words, compiletoflash and compiletoram. By running compiletoflash, any new word definitions are saved to flash rather than ram, allowing those words to be stored permanently as part of Forth. This is a really nice feature. There is also a word eraseflash that allows you to start from the original installed words, and someone has come up with a word called cornerstone that allows you to erase down to that point if you no longer need additional definitions.

If you have never seen Forth, it’s a stack-based interpreted programming environment that is conceptually quite simple. Numbers or addresses are passed on a stack as parameters to words (the equivalent of functions in other programming languages) to allow the words to perform the desired operations. Words are built from very simple building block words into more complex words by calling the primitive words in the desired order. New words can then call these words to do more complex things. Each time a new word is defined (in terms of existing words) it is compiled into a dictionary much as you would with a new word in English. As you are free to call the words whatever you like, you end up building a stack-based domain-specific programming language tailored to the problem you want to solve.

For example, you might make words that control a servo motor using pulsed-width-modulated timer. The primitive words would put the right numbers into the timing registers, and you would build your way up to having words that might address motors 1, 2, … n to turn a certain number of degrees. The program to turn the third motor by 30 degrees might look something like

3 motor 30 degrees turn

Words definitions tend to be short and closely linked to one another, because the overhead for defining a word is very small. Code tends to be fast, and takes up a small amount of memory, which is very advantageous when working with a microcontroller. You’ll see what I mean when I write the code further along.

So anyway, back to setting up the board to operate at high speed with the phase-locked loop. When I tried to use the word 72MHz as written, it would crash the board, and when that happens all the benefits of having an interactive programminh environment like Forth goes away. So I decided to move away from that code a little and start from scratch using the user manual for the STM32F103 chip. Upon looking up the appropriate registers, I was able to set the right bits in the registers that control the clocks on the chip, but it still crashed, producing a jumble of non-ascii characters on the screen and then not responding to typed text.

After many hours I worked out the problem: the original code was writing to the USART port (or serial port) 1, whereas on the STM32P103 the communications work on USART2. As the baud rate changes when the processor speed changes, the serial communication speed became all wrong, even though I thought I had fixed that (because I had fixed it for the wrong port). Once I realised this, it was a very easy fix to make the code work, and now I have 8MHz and 72MHz words that can change the speed of the processor on the fly, while keeping the baud rate at 115200 baud. Here’s the code:

8000000 variable clock-hz \ the system clock is 8 MHz after reset

$40010000 constant AFIO

AFIO $4 + constant AFIO_MAPR

$40013800 constant USART1

USART1 $08 + constant USART1_BRR

USART1 $0C + constant USART1_CR1

USART1 $10 + constant USART1_CR2

$40004400 constant USART2

USART2 $08 + constant USART2_BRR

USART2 $0C + constant USART2_CR1

USART2 $10 + constant USART2_CR2

$40021000 constant RCC

RCC $00 + constant RCC_CR

RCC $04 + constant RCC_CFGR

RCC $10 + constant RCC_APB1RSTR

RCC $14 + constant RCC_AHBENR

RCC $18 + constant RCC_APB2ENR

RCC $1C + constant RCC_APB1ENR

$40022000 constant FLASH

FLASH $0 + constant FLASH_ACR

$40010000 constant AFIO

AFIO $04 + constant AFIO_MAPR

: baud ( u -- u ) \ calculate baud rate divider, based on current clock rate

clock-hz @ swap / ;

: 8MHz ( -- ) \ set the main clock back to 8 MHz, keep baud rate at 115200

$0 RCC_CFGR ! \ revert to HSI @ 8 MHz, no PLL

$81 RCC_CR ! \ turn off HSE and PLL, power-up value

$18 FLASH_ACR ! \ zero flash wait, enable half-cycle access

8000000 clock-hz ! 115200 baud USART2_BRR ! \ fix console baud rate

$0 RCC_CFGR ! \ remove PLL bits

CR ." Reset to 115200 baud for 8 MHz clock speed" CR

;

: 72MHz ( -- ) \ set the main clock to 72 MHz, keep baud rate at 115200

\ Set to 8 MHz clock to start with, to make sure the PLL is off

$0 RCC_CFGR ! \ revert to HSI @ 8 MHz, no PLL

$81 RCC_CR ! \ turn off HSE and PLL, power-up value

$18 FLASH_ACR ! \ zero flash wait, enable half-cycle access

8000000 clock-hz ! 115200 baud USART2_BRR ! \ fix console baud rate

\ CR .USART2

$12 FLASH_ACR ! \ two flash mem wait states

16 bit RCC_CR bis! \ set HSEON

begin 17 bit RCC_CR bit@ until \ wait for HSERDY

$0 \ start with 0

\ %111 24 lshift or \ operate the MCO from the PLL

%111 18 lshift or \ PLL factor: 8 MHz * 9 = 72 MHz = HCLK

%01 16 lshift or \ HSE clock is 8 MHz Xtal source for PLL

%10 14 lshift or \ ADCPRE = PCLK2/6

%100 8 lshift or \ PCLK1 = HCLK/2

%10 or RCC_CFGR ! \ PLL is the system clock

24 bit RCC_CR bis! \ set PLLON

begin 25 bit RCC_CR bit@ until \ wait for PLLRDY

72000000 clock-hz ! 115200 baud 2/ USART2_BRR ! \ fix console baud rate

CR ." Reset to 115200 baud for 72 MHz clock speed" CR

;

Again, if you have never seen Forth, this might look a bit strange. The : character starts a new word definition, with the name of the word being the first word after the colon. A semicolon ; terminates the word definition. Then, if I load these definitions, I can simply type the name of the word 72MHz and the machine will start running at that speed. Backslashes indicate comments, as do the parentheses immediately after the word definition. These parentheses comments are special and are called stack constants because they remind the programmer of how many inputs need to be on the stack before the word is called, and how many remain after the word has finished running.

The constant definitions at the start of the code encode the addresses of various important registers. So after loading this file, if I were to type in AFIO_MAPR, then the address of the alternate function input-output register, $40010004 would be placed on the stack. One neat thing about Forth is how flexible it is in terms of its representation of words. For example, the word lshift is defined to take a number on the stack and shift its binary representation by a given number of bits to the left. This is like the C operator <<. So the code %011 24 lshift takes the number 3 (the % symbol represents a binary number) and shifts it left by 24 spaces, leaving the end result on the stack. So in the 72MHz word, we are able to shift the desired bit pattern into the correct locations as numbers and then logically OR the numbers together to give the number we want to put into the register to do what we want. The word that does the storing of the number into the register is ! (pronounced ‘store’). The word @ (pronounced ‘fetch’) gets the data from an address placed on the stack, so AFIO_MAPR @ would get the value currently stored in that register.

Now you may be thinking ‘lshift is a very unwieldy operator compared to <<‘. Well, one of the nice features of Forth is that if you don’t like it, you can change it easily, by defining : << ( n1 n2 --) lshift ; — again, the stuff between the parentheses in the definition is a stack comment and not code. Then you could type %011 24 << to get the same effect as lshift. The ease with which new words can be defined is either a great strength or a great weakness of the language, depending on your point of view. For some, it makes the language easily capable of conforming itself to the problem at hand. To others, it prevents the language from ever being properly standardised. Both points of view can be viewed as the correct one.

If you make a definition for a word init, mecrisp knows that it must, when stored in flash, execute the contents of that word when the controller is first booted. This allows a programmer to make a turnkey application that will run when the controller is switched on, and in this case if the word 72MHz is contained in the word init then it will be run on bootup, and the board will start running at full speed. Then, if the user wants to go back to 8 MHz operation, they can execute the 8MHz word interactively and the processor will drop back down to 8MHz.

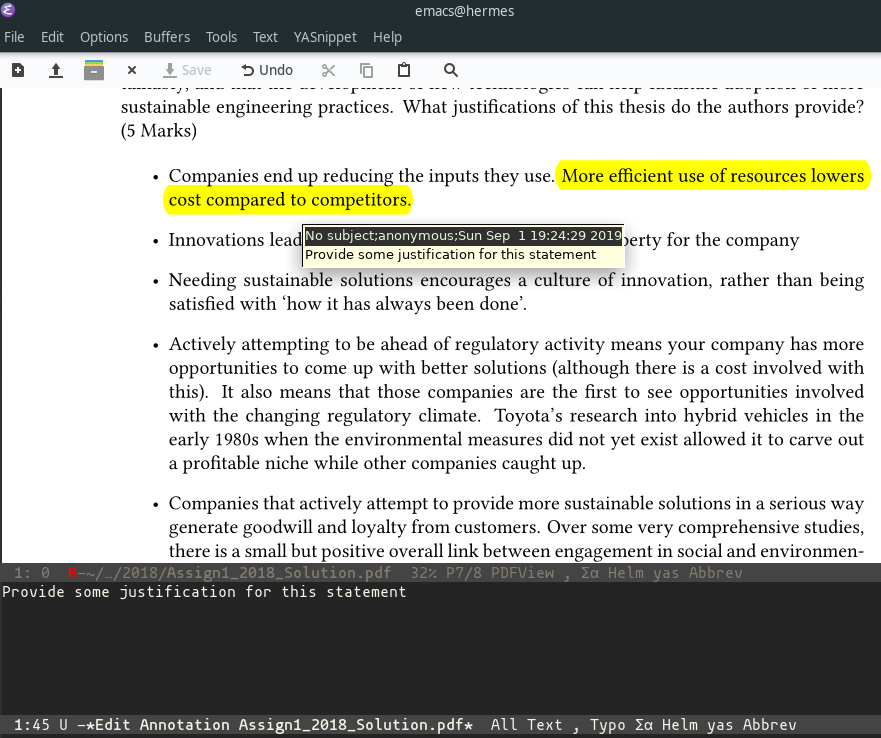

Developing in Forth is very different to the C or arduino workflow commonly used for these microcontrollers. In the latter case, development is done on your pc, compiled to a binary program that is uploaded to the board if it compiles correctly, then executed, perhaps using a hardware debugger to ensure it’s doing what you thought it should be doing. In Forth, words are developed in RAM, tested in isolation and, when you are satisfied they work, are saved to flash from within the Forth interpreted environment. Development is done on the microcontroller via a serial terminal connection to a computer, but all the compiling is done in situ on the chip itself. In this way, you can use words like @ and ! to interrogate and change register settings in real time. Also, it’s very easy to write an assembler in Forth, allowing you to access the speed of assembly language from within Forth for those times when the overhead of the interpreter is too great (which with a processor as powerful as these is almost never, for my sorts of applications). When you get used to it, Forth can be a very powerful programming platform.

I’ve never really understood why this programming language never reached popularity in embedded programming circles. Forth has a reputation as a ‘forgotten’, or ‘old-fashioned’ language. People who say this forget how old C is. I guess C and its derivatives like arduino got a head start as a language that many programmers already knew from university courses, and I can see from an employer’s point of view it’s much easier to replace C programmers than Forth programmers — Forth code can be very idiosyncratic.

But for a small system like a microcontroller where codes are usually written by individuals or small teams, Forth’s interactivity and incremental debugging approach are very desirable characteristics. The biggest disadvantage, however, is that there is much less in the way of libraries for this language and, as in the case above, you end up doing everything at register level from scratch. Again, whether you find that an advantage or a disadvantage depends upon your viewpoint.

If you program microcontrollers and have not tried Forth, give mecrisp a try. I really enjoy programming microcontrollers this way. Who knows? You may, like me, never want to go back to the edit-compile-debug-upload-run way of doing things again!