New Daily Driver: the Odroid N2+

I have always had a soft spot for fanless ARM single-board computers (SBCs) because they are quiet, portable and consume very little power compared to a typical laptop or desktop machine. A typical desktop computer will consume from 100 to 500 Watts of power, while a typical laptop consumes 60 to 90 Watts. An ARM SBC can consume anything from 6 to 30 Watts, which is considerably less than either of the more common formats. They also have less in the way of hardware monitoring than intel-based CPUs, and can run linux, which is my preferred operating system.

Until fairly recently, however, these machines have been too slow to operate well as standard work computers because package availability was sloppy and memory and CPU availability were at the low end of what you would typically need to get the job done. Also graphic processor support, the bane of linux, is particularly bad for these devices, as they tend to have commercial GPU drivers (as phones are their main application market).

As I mostly use open-source software for my research, and my graphical needs are fairly simple, I have proved to my own satisfaction that I can use these boards to do real work, albeit with a performance penalty compared to a modern i5 or i7 intel chip laptop. My first arm machine was an Odroid XU4 which I brought with me on sabbatical and used for writing papers and reports over a 5-month period. The only problem I had with that machine was that it would get into funny states after updating the OS, and it required a fan. Subsequent to this, I purchased a Pinebook Pro, which I could use as a laptop but which was a slower than the XU4, making the experience a little too frustrating to persevere with in the longer term, though I still use it from time to time.

Now Hardkernal, the maker of the odroid machines, has a new ARM64 SBC which is more powerful than the XU4, the Odroid N2+. This device is marketed as an alternative to the Raspberry pi 4 (which I have not used), being more powerful and more expensive. I purchased mine for USD86 with a plastic case, wireless dongle, and 128 GB emmc card (note that if you are going to use a computer seriously, having as much solid state storage as possible is very helpful). The device comes with 4GB of memory which, as the old Rolls-Royce acceleration specs used to say, is `adequate’.

This device uses more power than the XU4, requiring 12V and 2 A, rather than 5V at 3A. But this is not so surprising given the extra speed of the newer device. It also is by default fanless, although a fan is available for high load applications. So far in using it for my work, the heatsink has not got much more than warm. Although the device can apparently be overclocked to 2.4 GHz, I have not attempted overclocking it.

Initially if you purchase the device from the hardkernel web site, the emmc chip comes with ubuntu mate installed as the recommended operating system. As I like manjaro better than ubuntu, after playing around a bit with the default I used etcher to implement a manjaro sway windowing environment that has been compiled specifically for this computer. After a successful install I noticed that the screen I was using with the N2+ (a QHD 32″ lenovo monitor) would flicker randomly, which was very irritating. In case it was a problem with the Wayland system, I installed manjaro XFCE, which uses X11 rather than Wayland, but when I tried the XFCE version of manjaro, the flickering still occurred. So after a couple of unsuccessful installs, I went back to the original Ubuntu mate installation, which does not cause the flicker problem on my monitor, presumably because hardkernel installed the correct graphics drivers.

I really like tiling window managers that you can control via the keyboard (hence my initial desire to use sway), so once I had mate installed and the default user account removed I installed i3. The i3 window manager seems to work really well under ubuntu, and I was able to set things up just the way I like them. One of the things I don’t like about ubuntu and other Debian-based distributions is the slow turnaround time, as several applications require very up-to-date versions to operate properly (like my University’s owncloud server). However I was pleasantly surprised this time that most programs installable by apt were able to work without causing me problems because of their age.

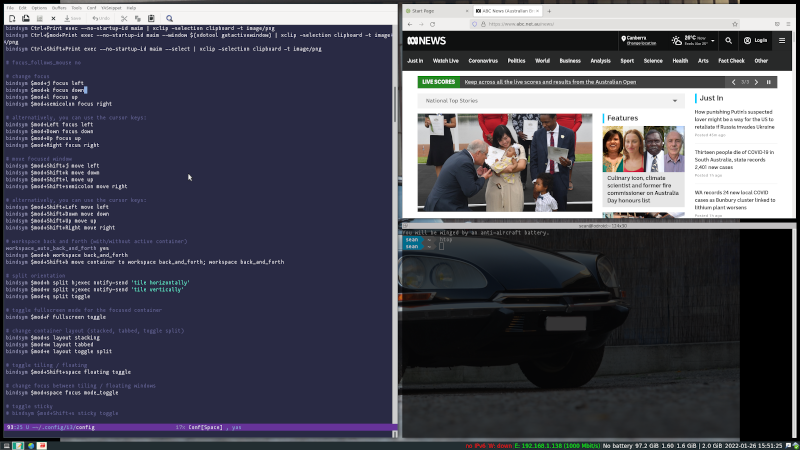

Here is a picture of what the configuration looks like. The image shows emacs, a translucent shell window (terminator, using powershell) and a web browser all open on the same workspace. The little icons on the bottom right show the other three workspaces that can be used.

Figure 1: i3 configuration

Because i3 is pretty lightweight compared to many window managers, the transition between workspaces and switching between applications is very fast. Using the emacs daemon makes editing very fast too. Once you get used to it, the keyboard-driven workflow associated with i3 and emacs is pretty hard to beat.

In total, with the blind alleys caused by trying the other distros, it took about 10 hours to completely set up the N2 the way I want it. Now I can use all the tools that I use on the intel laptop for my research work, and apart from taking a little longer to load programs, I don’t experience much lag at all compared to my i7 laptop. I was able to connect to my cloud service and to run all the codes I need to, either using snaps, apt, or in a couple of cases compiling from source. The experience is no worse than my usual linux installation experience (best described as me trying lots of permutations of random things based upon internet searches until something works). My existing i3 and emacs configurations were basically able to be transferred directly to the new computer with very few changes necessary. Because all my work in progress is on the cloud, this means that I can work on my project either on my laptop or on this SBC with seamless results, as I have the same applications installed on both machines.

In summary, I’m impressed. This blog post was written on it using emacs org2blog. It’s possible that I might get bored or frustrated and stop using this machine for work, in which case it will be used as a lab device for transferring data from instruments, or as a connected diary device. But at the moment I can’t much tell the difference between working on this machine and working on my laptop, and that’s a very good sign. It’s really impressive how far ARM64 support has come in linux. For a total outlay of less than AUD200, this is a really fun-to-use laptop replacement, provided you have access to a HDMI monitor and as long as you don’t mind shutting it down between moves (because it does not have a battery). 4GB is not a lot of memory, but in linux I have yet to reach a limit that affects my work in terms of available memory.

The small size of this machine means that, with a big rechargeable battery, it could be made into a very nice portable computer provided you have access to a TV or monitor with HDMI support, which is pretty much everything these days. I have some ideas about form factors that I hope to have time to try out one day…